Let’s find out real words from Harry Potter that are also in the dictionary. Ready?

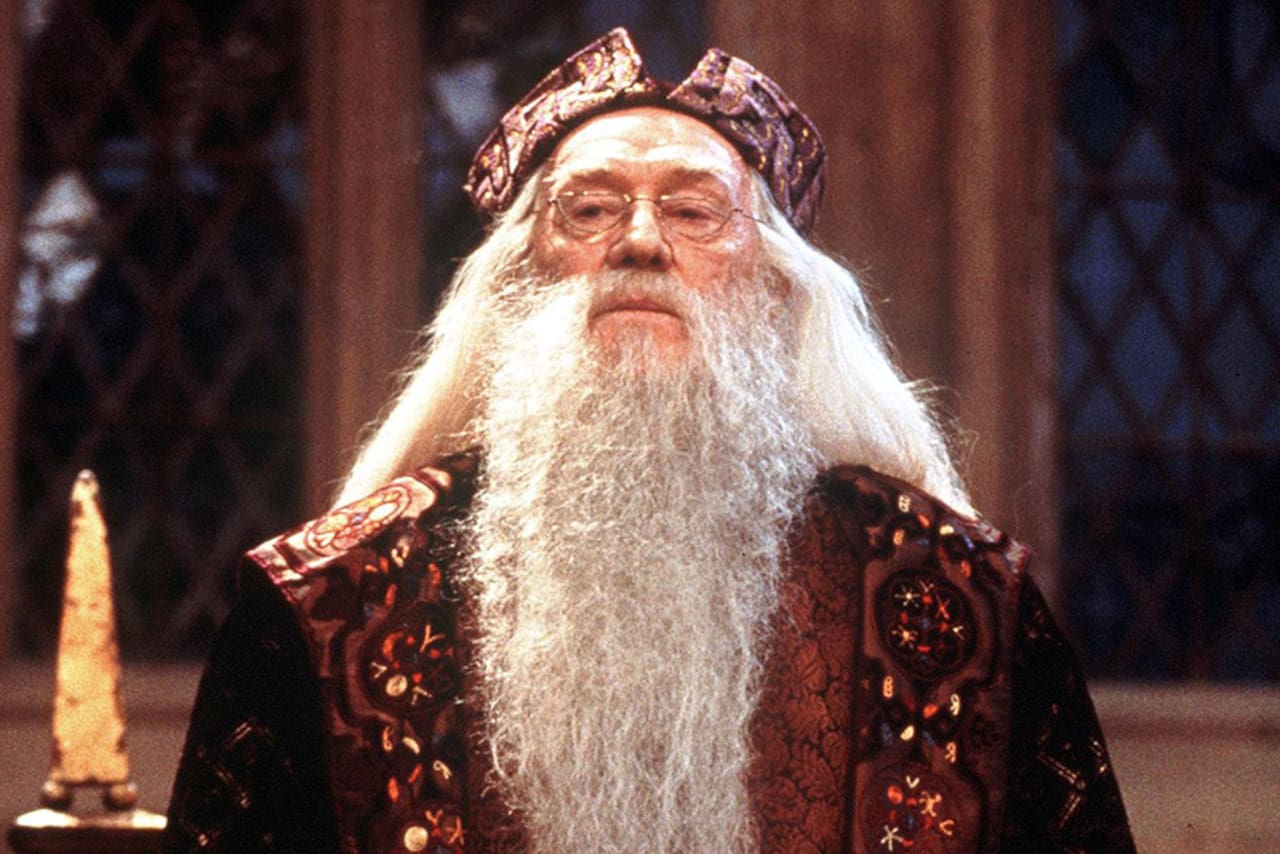

Dumbledore

Sometimes, the connection between a borrowed name and the character that bears that name isn’t always clear. Dumbledore, the name given to the headmaster of Hogwarts and one of the preeminent wizards of the Potter universe, is an 18th-century word for a bumblebee.

Dumble- was a prefix that was used to refer to various insects, and it has close cousins in humble-, bumble-, and dummel-, which some etymologists tie to dumb. Dore, or dor, is a word that dates back to almost 700 AD and refers to bees or flies. Bumblebees, with their bobbing, wavering, slow flight, might have looked dull or lazy, which accounts for the combination of dore and the dumb-adjacent prefix dumble-.

Muggle

The Harry Potter world is divided into the magical and the mundane, and J.K. Rowling created an entire vocabulary to separate the wizarding world from the Muggle world. Among those words was Muggle. A Muggle is a non-magical person. It’s a noun (“The Dursleys are Muggles”) and can be used attributively (as in “the Muggle world,” above).

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Rowling coined Muggle and probably based it on the earlier noun mug, which refers to a foolish or stupid person (though it goes without saying that foolishness or stupidity is not a hallmark of Muggles).

But Rowling wasn’t the first to coin the word muggle. There is an earlier muggle that is no longer used: it was a synonym of sweetheart.

It’s not clear where this muggle originated, because it was fairly informal—one 1622 treatise on domestic duties warns husbands against calling their wives by “names more befitting beasts then wiues, as Cole, Browne, Muggle, &c.”—and it not particularly long-lived. It had passed out of use by the 1700s.

Squib

In the Potter universe, there is a person who straddles the line between the wizarding world and the Muggle world, and that is a squib. Squibs are people who are born to wizarding parents, but who have no magical abilities of their own. In the Harry Potter world, squibs are rarer than wizards and witches who are born to Muggle parents.

Much like Muggle, the Potteresque squib shares space with an older squib, but unlike Muggle, Rowling’s squib and the real-world squib are related.

Squib first entered English in the 16th century, and one of its earliest meanings was “a firecracker.” (Yes, there were firecrackers in 16th-century England—fireworks themselves go back to ancient China.) Squibs in the 1500s were not much different technologically speaking from firecrackers today: small paper tubes filled with gunpowder.

It gained several new meanings very early on: a small firework that goes off with one flash of light and is over before you even realize it’s begun certainly lends itself to lots of metaphorical comparisons to disappointment. One early meaning was for a petty or insignificant person, likely based on the smallness of the firecracker.

The tie between the word squib and disappointment only grew as time went on: the phrase damp squib was coined later to refer to someone or something that promised much, but delivered very little.

Damp squib is more common in British English , which is Rowling’s native dialect, than it is in American English, and it is likely that she borrowed on both the sense of disappointment as well as the insignificance of the squib when she decided to use the word for those who had great magical potential, but turned out to be duds.

Basilisk

Most people know that some of the creatures mentioned in the series, from unicorns to werewolves, weren’t invented by Rowling, but they give her credit for creating creatures that have actually been discussed for hundreds of years.

One such creature is a major player in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets: the basilisk. The basilisk (also called a cockatrice in medieval mythology) goes back to medieval Greece and Rome; it is supposedly a serpent hatched from a chicken’s egg, whose hissing drives away all other serpents, and whose look (and breath!) were fatal. (In the Potter universe, those who see a basilisk indirectly—reflected in a mirror or a puddle, for instance—are not killed outright, but are merely turned to stone.)

Basilisk showed up in English in the 1300s, and comes ultimately from the Greek word basileus, which means “king” (likely because in the ancient world, the basilisk purportedly had a spot or a crest shaped like a crown on its head).

It was a creature that a variety of writers used, from Shakespeare (“It is a basilisk unto mine eye / Kills me to look on’t.” —Cymbeline, ca 1611) to Dickens, who compared a housemaid to the deadly serpent (“But to be quiet with such a basilisk before him was impossible.” —Barnaby Rudge, 1841). But the basilisk isn’t all mythology and metaphor: we borrowed the word to refer to a particular North American lizard that is in the same family as iguanas, and which can inflate and deflate a crest on its head at will.

Hippogriff

We’re introduced to the hippogriff in book three of the series, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. As Rowling explains, a hippogriff is a creature that is part horse and part griffin (which is, itself, part eagle and part lion), and the hippogriff first is discussed in ancient Greek mythology.

In spite of this, the word hippogriff didn’t show up in English until the 1600s, when the hippogriff was featured in a very well-known Italian epic poem called Orlando Furiosa. In the poem, the wandering knight Ruggiero rides a hippogriff (which is more like an eagle-headed pegasus than Potter’s Buckbeak).

Orlando Furiosa brought the hippogriff back from the pages of antiquity, and it occasionally featured in 19th-century heraldry. The word is a blend of the Greek ippo- (which is related to the Greek hippos, or “horse”) and grifo (which is from the Latin gryphus and which means “griffin”).

Nagini

Rowling didn’t just pull creatures from Greek and Roman mythology. The large snake that accompanies Voldemort, Nagini, shares a name with the great semi-divine serpentine creatures that are sometimes worshiped (and sometimes feared) in Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain mythology.

Nagini is the feminine form of the Sanskrit word nāga, which means “snake.” The Sanskrit word was borrowed into English in the late 1700s, and showed up in translations of Buddhist and Hindu texts.

Naga also came to be used in English of snakes, and particularly the cobra. In fact, one of the taxonomic genera that cobras belong to is Naja, a Latinization of the Sanskrit nāga.